When I first came to the Lehigh Valley in 1981, I got to know many local residents who shared with me memories of their youth in the early 20th century. One was a local figure of some note in a well-known local business, and another was an employee in that man’s business. Both had been born in Allentown and are now deceased.

As we talked, one name came up frequently: turn-of-the-century filmmaker and Wilkes-Barre born Lyman H. Howe (1856-1923). Each recalled as boys attending Howe’s travelogue films with footage of Africa, Switzerland, and far-away states of America like California. They implied that it gave them an interest in the exciting places that existed beyond the Lehigh Valley. Later, scrolling through the microfilm of old local newspapers, I would come across advertisements for shows of Howe’s films. At times it would refer to him as “Professor” or “Lecturer.”

Lyman H. Howe

So, who was Lyman Howe, a movie showman who was showing films when Thomas Edison was making westerns in the wilds of New Jersey, and Hollywood was in its infancy? Well, it might be fair to say he was part of the generation of inventor entrepreneurs that flourished in that era of Bell and Edison. Although largely a footnote for most people today, he is recognized among some film historians as a pioneer. The best book on Howe is “High-Class Moving Pictures: Lyman H. Howe and the Forgotten Era of Traveling Exhibition 1880-1920,” by Charles Musser with Carol Nelson; Princeton University Press, 1991.

Lyman Hankes Howe was born in Wilkes-Barre on June 6, 1856. His father, Nathan, was a building contractor. He came to Pennsylvania from his native Massachusetts to take advantage of the booming, coal-fueled economy. His mother, Margaret, was to have eight children of which he was the youngest. Growing up, Howe attended for two years Wyoming Academy, referred to in one source as a "secondary preparatory and business school.”

In his early years Howe was a traveling salesman and later created a business with a friend as a house and sign painter. In the general economic depression that followed the Panic of 1873 and the bankruptcy of his father’s business, he supported the family as a brakeman for the Central Railroad of New Jersey.

Howe clearly was an entrepreneurial sort of person. In 1883, with the general improvement of the economy, he entered with friend Robert M. Colborn the entertainment business. The pair acquired a miniature working model of a coal mine and went from one small Pennsylvania town to another, showing it off.

The high point, or perhaps the low point, was a failed appearance at Baltimore’s Masonic Hall. Deciding he would be better off on his own, Howe bought out his partner and, in the summer, took his display to Glen Onoko, a resort and waterfall near Mauch Chunk, now Jim Thrope. In the winter months he worked as a house painter. By 1890 he and a man named Haddock purchased a phonograph with a large speaker horn and, starting on March 10th of that year in Scranton, began to exhibit it along with the old reliable miniature coal mine.

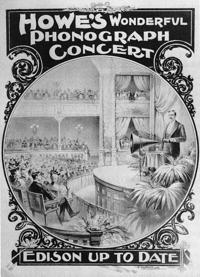

Advertisement for Lyman H. Howe phonograph concert

In April of 1890 Howe moved his entire operation to Allentown, the hometown of his wife, Alice Koehler. They occupied a storefront on Hamilton Street equipped with chairs. The Allentown Daily City Item newspaper reported that the first concert “was visited by people from every walk of life….and excited with wonder and curiosity of all who heard it…and attracted the best people.” The cost of admission was 10 cents. To liven things up, a recorded concert of the Allentown Band of a piece called “The Fisherman and His Child,” and a recitation of a colorful anecdote in Pennsylvania Dutch by the local congressman, were added.

The show moved on to South Bethlehem and Bethlehem and the press was enthusiastic. The Bethlehem Times called it bottled music: “Such it seems to be as though you drew the cork and set the voices of past and present free.” It added “everything can be distinctly heard in every corner of the room.”

Although Mr. Haddock drifted away, Howe continued to travel from small northeastern Pennsylvania town to small northeastern Pennsylvania town, putting on phonographic concerts. It may not have been Harold Hill and his 76 trombones but to people who had never heard one it seemed to work. A source calls Howe “among the first to give full-length phonographic concerts.” It was at this point Howe began to call himself “professor.”

But Howe was not content to rest there. Apparently, he wanted to buy a kinetoscope, the new technology of its day from Edison but the inventor was not interested. In 1896 he attempted to lease something called a vitascope from an outfit named Raff & Gammon, but again had no luck. Refusing to be thwarted, Howe, with the aid of an electrician, invented his own projector that he called an animotiscope. Among his improvements was a second take-up reel. This enabled the showing of longer films.

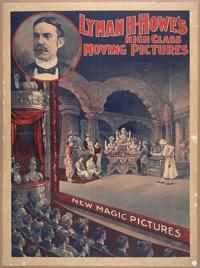

Howe’s first film premiered in Wilkes-Barre on December 4, 1896. A poster advertising it called it “Lyman H. Howe’s New Marvels in Moving Pictures.” Howe’s early films used some common techniques but others he devised. Howes’s portrait was featured, hair parted down the middle, bushy moustache, proper high collar bow tie and all, the perfect candidate for a barbershop quartet or maître de at a high-class hotel dining room. He even used the words “High Class Moving Pictures” in his advertising.

An advertisement for Lyman H. Howe's "High-Class Moving Pictures"

The staples of Howe’s films in those early years were travelogues and newsreels. Some were accompanied by photographs for sound. By 1901 he was creating his own films and was the first person to incorporate backstage sound effects in his movies. In those first decades of the 20th century the public flocked to see them. Among his most popular films were films of the Olympic Games, the wedding of King Alfonso XIII of Spain, and in 1905 a visit of President Theodore Roosevelt to Wilkes-Barre.

By 1903 Howe had six traveling movie companies based in Wilkes-Barre. In 1909 he joined fellow film producers Burton Holmes and Fred Niblo in something called Motion Pictures Patent Company. Howe’s films were soon being seen in all the major cities in the United States and Canada from 1912 to 1919. As early as 1911 Howe was making films from airplanes. During World War I his newsreels from the battlefield attracted large audiences.

According to several sources Howe’s best-known film is titled “Lyman H. Howe’s Famous Ride on a Runaway Train.” Filmed from a moving train on a steep slope, notes one source it produces a “vertiginous effect which influenced 'This is Cinerama,'” a 1952 film narrated by Lowell Thomas that took viewers on a wild ride. Several years ago, this film by Howe was discovered in of all places the New Zealand Film Archive, now known as the Nga Taonga Sound and Vision.

Lyman H. Howe died at age 66 on January 30, 1923, in Brookline, Massachusetts. According to one source by 1922 “he had virtually withdrawn from all business activities… struggled with a protracted illness and entered a Christian Science sanatorium on June 22, 1922.”

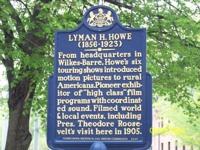

Historical marker in Wilkes-Barre for Lyman H. Howe

Howe was buried at Oak Lawn Cemetery, Hanover, Luzerne County. His company continued to exist into the 1930s, showing short films about the Great Depression. On September 18, 2000, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission erected an historical marker at Wilkes-Barre in his honor. The generations who saw his work never forgot him.