Andrew Mitchell warns large numbers in Somalia could die

- Published

Development Minister Andrew Mitchell has told the BBC "large numbers of people are in danger of dying" in Somalia if the international community does not give the drought-ridden country more help.

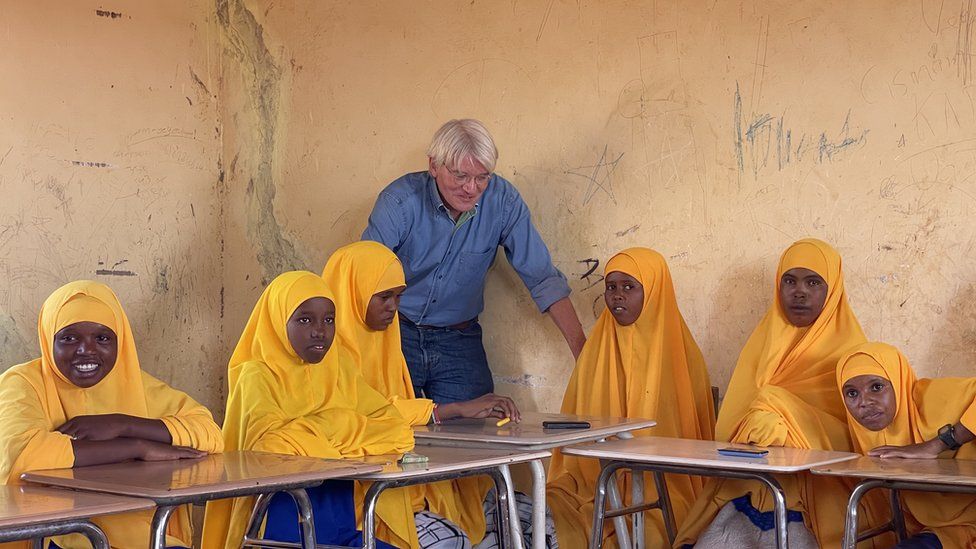

On a visit to western Somalia, he announced the UK was providing a £14m package of new humanitarian and security aid for people facing famine after climate change was blamed for the worst drought in 40 years.

Mr Mitchell said it was "unacceptable" that the world was "neglecting people who are dying in the Horn of Africa" because so much aid money had been diverted to Ukraine. He insisted Britain was showing leadership by tackling both issues at the same time despite cuts to the UK foreign aid budget.

But he admitted it was "a difficulty" that the Home Office was spending billions of pounds of aid on asylum seekers, and hoped "it won't go on forever" because "it does constrain" the UK's humanitarian response overseas.

He revealed he was setting up a new joint committee with the Treasury to scrutinise aid spending across government.

Mr Mitchell also announced a new aid partnership with Saudi Arabia, matching £1.7m in UK support for the World Food Programme in Somalia.

'Profoundly malnourished'

He was speaking in Dollow, on the parched plains of western Somalia, a place he last visited 11 years ago when he was International Development Secretary.

The town near the border with Ethiopia has become a magnet for people whose livestock and livelihoods have been devastated by the drought. There are now some 134,000 people in two large camps for internal refugees.

Hamdi Mohamud, 18, goes to a school here that's been supported by British aid. "Sometimes I go to sleep hungry and sometimes I cannot buy the exercise books I need for school," she told us.

"But I motivate myself. I tell myself that some day things will not be like this, and in the future I will be a very important person and help my people."

International experts are expected to decide shortly if Somalia has met the strict conditions needed to declare an official famine.

Mr Mitchell arrived in great secrecy and security because of the threat from al-Shabab, Islamist militants who control much of Somalia.

He said the devastating drought - brought on by the failure of four consecutive rainy seasons - meant "the resilience of the population is low". There were now, he said, "a million children who are profoundly malnourished".

Of the new funding, £6.7m will provide food, water and healthcare to half a million of Somalia's most vulnerable people. Some £3.8m will go on a special insurance scheme to help protect farmers against future droughts.

And £1.5m will help support Somali troops fighting al-Shabab.

'World must help Somalia'

Mr Mitchell insisted there had been "good progress" in pushing back the militants, whom he said posed "a threat to Somalia, but also a threat to us on the streets of London and Birmingham".

This means the UK has given Somalia about £62m this year. This is still less than the £101m it spent last year and the £232 it gave in 2020.

Mr Mitchell said: "The key issue here is co-ordination and making sure that everyone else steps up to the plate - alongside Britain - to deliver for people here, who are in danger of dying in very large numbers if the international community doesn't react properly."

He accepted that international rules allowed the UK to spend aid money supporting asylum seekers in their first year in Britain.

But he added: "It is a difficulty and I hope it won't go on forever because it does constrain the [aid] spending."

He said the Treasury had accepted this by, in effect, providing the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office with £2.5bn in compensation.

He said the international community had to support countries like Somalia as well as Ukraine. "From the view of Africa, if a lot of money has been diverted to look after people who are suffering from this appalling war in Ukraine, but we are neglecting children who are dying in the Horn of Africa, that is something which is unacceptable.

"This is an unstable part of the world. We've got to beat back the terrorists, and we are… And we have got to address the effects of this drought both in the long term through climate change work, and in the short term now going to the aid of desperate people and saving lives."

El-Khidir Daloum, director of the World Food Programme in Somalia, welcomed the new UK aid, but said more was needed.

"This is not a normal drought," he said. "This is a real climate change crisis. We have to make sure we are saving life. We have to make sure that we are averting the worst to come in terms of the famine.

"We have to make sure that the 1.8m children who are malnourished are rescued and are not dying. But we also have to look for a resilience response, we have to look for a climate adaptation response. Otherwise, the crisis is going to be multiplied."

Related Topics

- Published15 November 2022

- Published4 October 2022

- Published27 September 2022