Only David Reich’s eyes were visible as he inspected the batch of bones. Reich, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School, wore a hooded white clean room suit, cream-coloured clogs, and a blue surgical mask. On a counter in front of him lay a row of bone fragments. He pointed out a strawberry-size chunk: “This is from a 4,000-year-old site in Central Asia — from Uzbekistan, I think.”

He moved down the row. “This is a 2,500-year-old sample from a site in Britain. This is Bronze Age Russian, and these are Arabian samples. These people would have never met each other in time or space.”

Reich hopes that his team of scientists and technicians can find DNA in these bones. Odds are good that they will.

In less than three years, Reich’s laboratory has published DNA from the genomes of 938 ancient humans — more than all other research teams working in this field combined. The work in his lab has reshaped our understanding of human prehistory.

“They often answer age-old questions and sometimes provide astonishing unanticipated insights,” said Svante Paabo, the director of the Max Planck Institute of Paleoanthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

Reich, Paabo and other experts in ancient DNA are putting together a new history of humanity, one that runs in parallel with the narratives gleaned from fossils and written records. In Reich’s research, he and his colleagues have shed light on the peopling of the planet and the spread of agriculture, among other momentous events.

In a book published recently, Who We Are and How We Got Here, Reich, 43, explains how advances in DNA sequencing and analysis have helped this new field take off. “It’s really like the invention of a new scientific instrument, like a microscope or a telescope,” he said. “When an instrument that powerful is invented, it opens up all these horizons, and everything is new and surprising.”

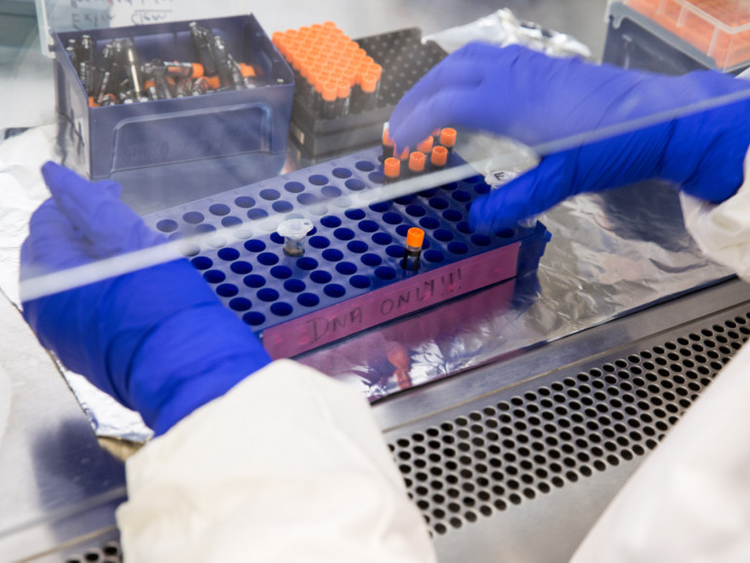

Reich oversees a team with many different skills, from genetics to mathematics. But the “clean lab” is where the raw material for all their work —ancient DNA - is recovered. The head-to-toe suits that the researchers don in an airlock each morning ensure that no stray flake of skin or bead of sweat contaminates the bones with modern DNA. Each night the entire lab is bathed in gene-destroying ultraviolet light.

The clean lab feels as if it belongs in a computer chip factory. But Reich has not forgotten that these are human remains, not widgets on a conveyor belt. “This is a bone from a person’s body who lived 4,000 years ago, and we’re destroying it,” he said, gazing down at the Uzbek remains. “I think we need to do well by the individuals we’re studying.”

Doing well means understanding who these people were, and how they were linked to one another — and to us.

(BEGIN OPTIONAL TRIM.)

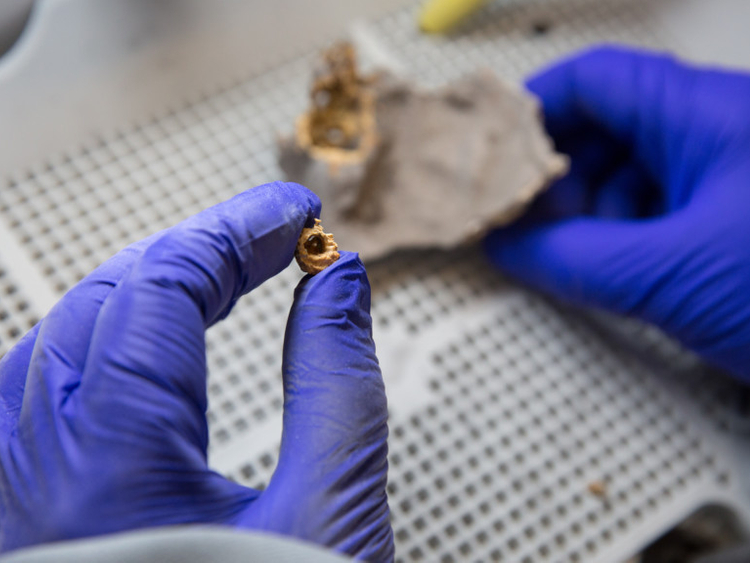

Standing next to Reich was a suited technician, Ann Marie Lawson. She picked up the Uzbek bone and lowered it into a box, which she covered with a clear plastic lid. She pushed her gloved hands through two rubber-lined holes on its sides.

She picked up the bone in her left hand; with her right hand, she switched on a sandblasting hose and pointed it at the bone. An outer layer of dirt flew upward, quickly sucked away by a fan in the box.

Lawson stopped to inspect the freshly white bone. It came from the base of a skull, and deep inside was the inner ear. The bone that surrounds the inner ear turns out to be the best place in the body to search for ancient DNA. Lawson began sandblasting again, chiselling away chunks of bone. Eventually, she was left holding a remnant only as big as a grain of rice. “That’s the mother lode,” Reich said.

(END OPTIONAL TRIM.)

Reich grew up in Washington, the son of the novelist Tova Reich and Walter Reich, the first director of the Holocaust Memorial Museum and now a professor at George Washington University.

Reich began studying sociology as a Harvard undergraduate, but later he turned to physics and then to medicine. After graduating, he went to Oxford to prepare for medical school. There he met Dr David B. Goldstein, who at the time was comparing the DNA of living people for clues to what their distant ancestors were like.

“When I first met him, he was obviously smart, but he gave an impression of being a little bit shy and not having a very forceful personality,” Goldstein said. “It turned out that’s the most misleading impression he could possibly give. He knows exactly what he wants to do.”

It was obvious that his student was captivated by the research. But Goldstein had come to view it as a scientific dead end. “I said, ‘My God, don’t spend your career on human evolutionary genetics,’” recalled Goldstein, who now studies disease genetics at Columbia University. “He just listened very politely and wasn’t persuaded an iota,” he added. “He wasn’t just proven right. He was proved dramatically right.”

Abandoning medical school, Reich continued with genetics research and was hired by Harvard Medical School in 2003. By then, he had developed a close partnership with a mathematician named Neil Patterson, who had come late in life to genetics, after 20 years working as a cryptographer in British intelligence and then joining a hedge fund.

Reich appointed Patterson deputy head of the newly formed genetics lab, and together they began developing new statistical techniques to plumb genetic data for hidden patterns. The two researchers devised a way to determine whether a single population descended from two or more distinct groups. Collaborating with researchers at the Center for Cellular and Molecular Biology in Hyderabad, India, they put their method to its first big test.

Analysing DNA from hundreds of villages, they discovered that just about every living Indian descends from two distinct groups. One, which the researchers called Ancestral North Indians, is related to Central Asians, Near Easterners and Europeans.

The second group, Ancestral South Indians, is a mysterious population that is not closely related to any living people outside of India. The two populations mixed together, Reich estimated, 2,000 to 4,000 years ago.

As Reich and his colleagues gained attention for their new methods, they got an extraordinary invitation: to study the DNA of Neanderthals.

The invitation came from Paabo. In the 1990s, he had pioneered methods to extract ancient DNA from fossils dating back tens of thousands of years. While he studied many extinct species — such as cave bears, mastodons and ground sloths — Neanderthals were his deepest passion.

Fossils of these heavy-browed individuals date back over 200,000 years in Europe and the Near East. They made tools, weapons and even cave art. But they vanished about 40,000 years ago.

Paabo gradually filled in gaps to reconstruct the entire Neanderthal genome. In 2006, he invited Reich’s team to help figure out how modern humans and Neanderthals were related. Reich threw himself into the project, and over the next few years, the scientists made a series of landmark discoveries.

The DNA of Neanderthals indicates that their ancestors split from our own about 600,000 years ago. But Reich’s tests revealed that living humans outside of Africa still carry traces of Neanderthal DNA.

How is that possible? Before Neanderthals became extinct in Europe, they encountered and interbred with the ancestors of modern humans as they departed Africa.

As the scientists searched in more fossils for Neanderthal DNA, they got another surprise. In 2010, a nondescript pinkie bone recovered in a Siberian cave called Denisova yielded the entire genome of a previously unknown, and extinct, lineage of humans.

The Denisovans, as they came to be known, split off from Neanderthals about 400,000 years ago, genetic analysis revealed. Denisovan DNA has turned up only in a few additional teeth discovered in that Siberian cave. The oldest such fossils date to over 100,000 years old; the pinkie bone belonged to a Denisovan who lived 48,000 to 60,000 years ago.

Reich and his colleagues discovered that Denisovans, like Neanderthals, left a genetic legacy in living people, mostly in Australia, New Guinea and Asia.

Ancient DNA has summoned the genetic shadows of a long-vanished people, one that fossils alone could not reveal. Many scientists now suspect that ancient DNA will reveal other extinct kinds of humans.

“The discovery of Denisovan DNA was a landmark in my thinking about ancient DNA,” Reich said. “It can reveal things about the past that are completely unexpected, that are not dreamed of in our philosophy.”

Reich’s voyage through prehistory left him wondering about what DNA could reveal about more recent events. Museums around the world were loaded with bones of people who lived within the last 20,000 years, after all.

Since those remains were younger, they would be more likely to still have some DNA in them. To begin retrieving it, Reich retooled his laboratory, copying Paabo’s facility in Germany to the last detail.

But in important ways, Reich broke from the standard scientific strategy for searching for ancient DNA. Paabo and other experts typically examine many fossils to find a rare one packed with DNA. They then try to reconstruct the entire genome. Reich’s lab instead designed DNA “traps” that snag hundreds of thousands of genetic fragments from the human genome. The result is far from a complete genome sequence, but enough to divine ancestries and even get some clues about the traits of ancient people.

In 2015, the first results emerged from Reich’s new research pipeline. He and his colleagues published DNA from 69 ancient Europeans who lived 3,000 to 8,000 years ago.

According to their results, farmers with Near East ancestry displaced hunter-gatherers already living in Europe. Then, about 4,500 years ago, another wave of people arrived, descended from the horse-riding nomads of what are now the Russian steppes.

Less than three years since that study, Reich’s team has published a torrent of similar findings. They have traced the spread of the first farmers in the Near East, for example, and have tracked the rise and fall of various populations in ancient Africa.

While some of these results describe migrations across continents, Reich’s team also focuses on smaller regions to reconstruct the genetic makeup of the people over thousands of years.

Recently, for example, Reich and his colleagues published the DNA of people who lived on what are now the British Isles 3,500 to 10,000 years ago. It, too, tells a story. When the Ice Age glaciers retreated from the islands, hunter-gatherers moved in from what is now Europe. About 6,000 years ago, farmers with Near Eastern ancestry reached Britain, and mostly replaced the hunter-gatherers.

About 4,500 years ago, there was a sudden shift in Britain to new styles of pottery and metalworking, known collectively as the Beaker culture. Many experts have argued that farmers borrowed the techniques from the European continent.

But the DNA says otherwise, Reich and his colleagues found. While the Beaker culture spread from society to society on the mainland, it was brought to Britain by immigrants descended from the nomads of what are now the Russian steppes.

These people almost entirely replaced the earlier farmers. Today, British people trace 90 per cent of their ancestry to this immigrant wave.

Were it not for the genetic findings, “nobody would have believed the scale of the turnover,” said Ian Armit, a University of Bradford archaeologist who collaborated with Reich. “Archaeologists will need to get to grips with this 90 per cent replacement, and what this might really mean in human terms,” he said.

The Beaker people needed only to cross the English Channel to get to the British Isles. A far more spectacular voyage took place about 3,300 years ago, when humans first sailed to remote islands in the Pacific.

Reich and his colleagues have shed light on that migration by analysing ancient DNA from the skeletons of early Pacific voyagers. “It’s changed the game,” said Matthew Spriggs, an archaeologist at Australian National University, who has collaborated with Reich.

Until recently, many archaeologists argued that the ancestors of Pacific Islanders were related to the indigenous people of Taiwan. They had sailed south to the islands around New Guinea, the idea went, later mixing with the population, known as Papuans. Only later did their descendants sail east to Pacific islands.

This theory helped account for the kinds of languages spoken in the Pacific, the agriculture, and styles of pottery, as well as the mix of East Asian and New Guinea DNA found in the islanders.

Spriggs and other archaeologists provided Reich with bones from Vanuatu and Tonga, and his team succeeded in recovering DNA where others had failed. And what did it say about the prevailing theory?

“We found genetically that wasn’t right at all,” Reich said. He and his colleagues published their results in February in the journal Current Biology.

Instead, the people who first arrived on Vanuatu and other Pacific islands came directly from Asia without ever stopping in New Guinea. Only later did a wave of Papuans arrive. “We know now when that wave hits - it hits before 2,400 years ago,” Reich said. “And it’s a total replacement.”

And that second wave actually was made up of at least two migrations. The Papuans who came to what is now Vanuatu probably sailed from the Bismarck Islands. But the Papuans who arrived further east, in Polynesia, came from other islands, possibly New Britain.

As of February, Reich’s team has published about three-quarters of all the genome-wide data from ancient human remains in the scientific literature. But the scientists are only getting started. They have retrieved DNA from 3,000 more samples. And lab refrigerators are filled with bones from 2,000 more denizens of prehistory.

Reich’s plan is to find ancient DNA from every culture known to archaeology everywhere in the world. Ultimately, he hopes to build a genetic atlas of humanity over the past 50,000 years. “I try not to think about it all at once, because it’s so overwhelming,” he said.

–New York Times News Service