Making art can be a process of personal invention, and even reinvention. Just ask Sean Combs, or Puff Daddy, or P-Diddy or Diddy. Then there’s Andrew Warhola, who took off the last letter of his surname when he went from Pittsburgh to New York.

For the Japanese artist Hasegawa Tohaku (1539-1610), perhaps the first to propel his career by making himself anew, reinvention involved changing his name and weaponizing his ambition. Once a zen painter, he later emerged as the chosen artist for creating landscapes in the palaces of powerful warlords in the late 16th and early 17th century.

Before that transformation, Tohaku had been Hasegawa Nobuharu, a young man of common birth from the coastal town of Nanao, adopted by a family of fabric dyers. Nobuharu’s career began as a painter of Buddhist icons and Buddhist priests. The name Nobuharu came from his adoptive parents, who also gave him the name Matashiro.

Two of those early Buddhist portraits are in the show, one from 1572, another undated. Each portrait has a calm yet striking presence, with exquisite facial details and attention to the garments that defined the subject’s position.

Around 1571 Nobuharu disappeared (records suggest) and reemerged in 1589, at fifty, as a painter and decorator of Daitokuji, a Zen temple in Kyoto, the capital. This was a step up. Powerful patrons meant privileged positions. For Nobuharu, it meant a new identity. The renamed Hasegawa Tohaku would have a different status in society, which he held until his death in 1610.

Some saw Tohaku as an interloper, taking up the place that Kano Eitoku, the leading painter of his generation, had occupied right after Eitoku died prematurely in 1590. Tohaku’s new role as painter to the powerful was enhanced by the fact that many of Kano Eitoku’s paintings would be lost in the fighting between warlords that destroyed those palaces. Historians say that Kano’s followers worked hard to prevent Tohaku’s reputation from surpassing Kano’s and routinely attributed Tohaku’s work to other artists. Those attributions are still being corrected today.

But Tohaku did his own reputation-building. did his own reputation-building. As an oft-repeated tale tells it, in one Kyoto temple where he had been denied a commission and told by an abbot that a set of sliding doors was off-limits because it belonged to Buddha, Tohaku waited until the abbot left and painted a landscape on the doors. He then got the commission, the story goes—if you choose to believe it.

Now open at the Japan Society in New York, “A Giant Leap: The Transformation of Hasegawa Tōhaku,” is the first U.S. exhibition devoted to Tohaku. A major figure in the Momoyama period (1568-1615), his work serves as a cultural record, of the remarkable moments of the time: Westerners arriving, battles for power, new wealth, and artistic experimentation. The last show in New York to address this period was in 1975 at the Met.

Several of some dozen works have never traveled outside of Japan before, and, in fact, the exhibition opens with a work that did not travel. It’s the ink painting masterpiece Pine Forest, from around 1580, which is in the Tokyo National Museum. The monochrome landscape from his early period is being shown in facsimile (with photography thanks to Canon), and it is installed with rows of cushions that run the length of the room, for visitors who want to spend time with the work. The trees are sparse in the picture with snowy peaks in the background. Some sections have more empty space than paint, and it takes some adjustment to see the tree branches in the ink marks. The painter has shown you that less can be more, and less can also be hypnotically elegant. Zen here becomes more than a label.

The exhibition is serene in some places, dazzling in others, and sometimes confusing. The mystery isn’t why Hakegawa Nobuharu took a second name—the ambition of a small-town upstart explains that—but how he learned the range of styles in which he painted.

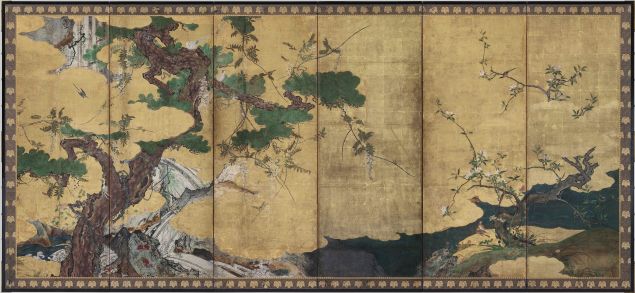

Take Flowers and Birds of Spring and Summer, from the 1580’s, a six-panel folding screen in ink, color and gold on gilded paper, which is now in a private collection in New York. Scholars using dates, signatures and stylistic details say that it is by Nobuharu. When you’re in front of it, “reading” from right to left, as the Japanese do, you move from delicate flowers on the thinnest of branches to a snarl of wood and green that still covers only part of the surface. Nature, as sparse and fragile as it is, is all the more worth observing against the gold.

Painting on a gold surface was a technique that was new in Kyoto then, and would have been hard for Nobuharu to learn in the small town of Nanao. Scholars think that Nobuharu learned that skill after he moved to Kyoto in 1571, and that he practiced it on paintings that have still not been identified before painting this work. They see this as the moment when Nobuharu became Tohaku, with emergence of Tohaku’s style for his new patrons.

Nature is more rugged than delicate in Horses at Pasture, from the Tokyo National Museum. Animals run and graze and laze around in a landscape that takes you, from right to left, through the seasons. When you look closely, as you must with all these images, they seem to have at least as much personality as the men riding or herding them. Perhaps that’s because they were more challenging or more fun to paint.

In another stylistic turn, Tohaku paints Chinese landscapes in a near-monochrome in ink with faint colors and gold in Eight Views of Xiao and Xiang. There’s no record of Tohaku (or Nobuharu) traveling to China, but who knows? A contemplative study of expanse and restraint, it’s a Japanese painting about the experience of looking at a Chinese painting, one of an infinite number of Japanese borrowings from China.

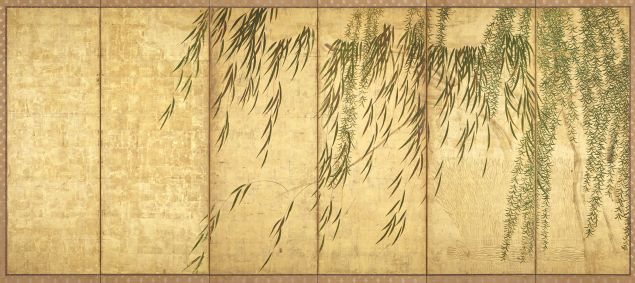

If those landscapes are the view from afar, the shimmering Willows in Four Seasons by Tohaku is a view up close. The willow leaves in six panels against a gold background are each a single stroke of paint. The picture’s meditative simplicity takes you back to Pine Grove in the first gallery. Zen on gold. How’s that for a paradox?